History of the Seminaarinmäki school garden and the Botanical Garden

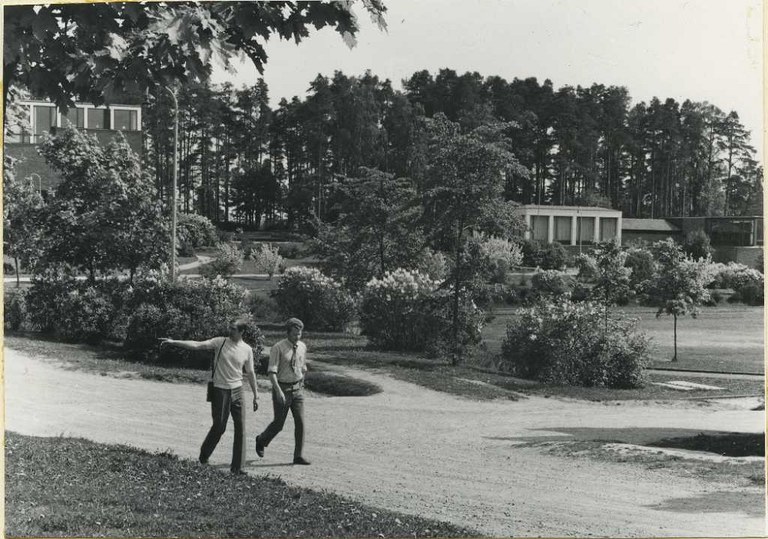

Seminaarinmäki is the only Finnish historic campus area that has remained fully integrated. All other campuses in Finland have been fragmented by urban construction as cities have penetrated the campus areas – either by introducing new buildings that are not part of the educational institution or by transforming school buildings to serve other purposes. Keeping the Seminaarinmäki campus apart from the rest of the city structure is largely owing to the founder and first director of Jyväskylä Teacher Seminary, Uno Cygnaeus (1810–1888). His ideal was a countryside seminary where the teacher institute was regarded as separate from the other activities in the town, while the location should also be at a distance from the core areas of the town. The Seminary was originally planned to be located farther away from the town centre.

For more information on the pictures, place the cursor on the image (under translation, this feature will be coming soon). If you are on a mobile device, select the image for preview by holding your finger or stylus on the image for a moment.

The origin of the Seminaarinmäki school garden

Jyväskylä Teacher Seminary was the first Finnish teacher seminary for folk schooling. It was established in 1863 in Jyväskylä, in rental premises in the area of the present Cygnaeus Park. Finland’s first state-funded school garden was established when new and permanent buildings were constructed for the Teacher Seminary on the fields of the Harju ridge on the outskirts of the town centre. The first construction period on Seminaarinmäki dated back to the years 1879 to 1883 when the brick buildings designed by Konstantin Kiseleff were erected on the hill.

From the very beginning, people started to make plans for a school garden in conjunction with the Teacher Seminary as well. In addition to its educational function, a plant collection was gathered for the garden. Thus, we could actually talk about a botanic garden since the 1880s already. The first garden plans for Seminaarinmäki Park were drafted in 1882 by L.A. Jernström, who was at that time the city gardener of Helsinki. Unfortunately, neither the original plan nor much related material (maps, photographs) have been preserved concerning this original plan for Seminaarinmäki Park. In any case, trees were preserved in their natural biotopes. The apple orchard became quite large. Toward the Mäki-Matti area a high wooden fence was built because in those days this residential area had a somewhat restless reputation. The Seminary also received some forest, field and meadow land beside the ridge (as a pasture for horses). Large cultivation areas were established on the former fields of the Mattila farmhouse. From the very beginning, the Seminary also employed some outside labourers and a gardener.

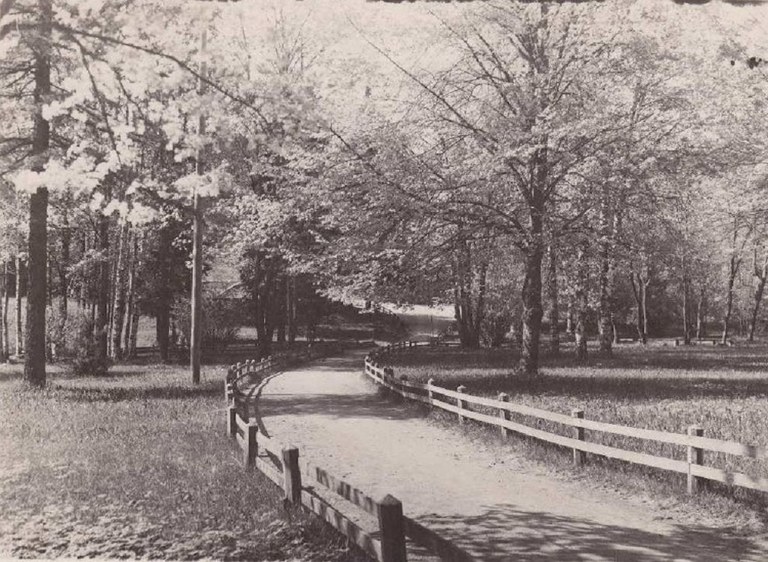

It can be concluded that the original plan followed at least partly the design principles of a German architect Gustav Meyer, as when working in Germany, Jernström had had contacts with Meyer, and there was a park construction boom in Germany at the end of the 19th century. The park boom reflected bourgeois tastes, in particular, and responded to the need for developing greenspaces for the growing cities. It is likely that at least Meyer’s design principles and ideals for landscape parks were copied in Seminaarinmäki Park. Such park designs aimed at creating freely growing landscaped wholes, a kind of ideal scenery with a harmonic and picturesque character. Parks were considered to have health-promoting and aesthetic educational effects – the purpose was to lead a visitor in a civilized manner through the resting places and path networks.

The most significant (and now lost) elements in the original Seminaarinmäki Park included a view of Lake Jyväsjärvi; there was a birch-lined walking strip leading down to the lake. There were also huge orchards with berry and fruit plants. On the beach, the Seminary had a pier for boats and a swimming facility. The current location of the Library featured a large orchard.

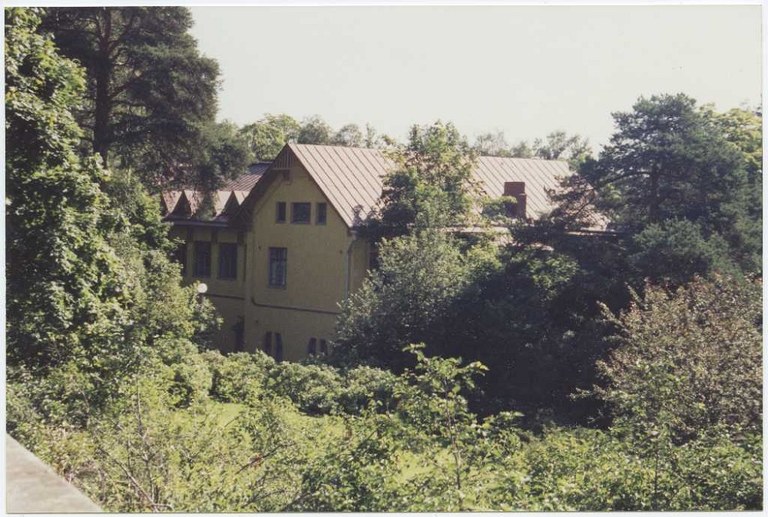

In general, there were no formal elements in the landscape garden of Seminaarinmäki. The only ones could probably be found right next to the buildings where ornamental plants and flower beds were usually kept so as to indicate the hierarchy of the landscape and highlight the integrity of the buildings. In contrast, the garden of the art nouveau building Villa Rana (1905) included more formal elements, such as shaped bushes.

The Moirislampi pond was originally a wetland area, which was then deepened to serve as a water supply for the construction stage of the Seminary. Later, the pond was enlarged, and it became a popular hangout for Seminary students. The pond was named Moirislampi, inspired by the freshwater flood lake Moeris in ancient Egypt. Later, an island was built to the pond, with a gazebo and bridges. The pond served as a venue for various celebrations and leisure activities. You could see the female students’ ‘nun procession’, circling the pond. Some students were said to throw their course books into the pond upon completion of the semester. The original Moirislampi was filled with land in the 1920s,and the site was turned into a ballgame field. The present Moirislampi is located elsewhere, on city-owned land.

Professor Harry Lönnroth has written about the student traditions of Moirislampi lakeside (In Finnish): JYUnity.fi

School Garden

Gardening instruction in the school garden was not very systematic at first. The focus at the Seminary was on learning practical gardening rather than on botany. The actual gardening instruction started in the 1890s, during a gardening boom in Finland in general. Gardening clubs were founded, and the first Finnish-language gardening magazine was published. The folk school system was also expanding at this time, and education was becoming more systematic. During the first decades of the 20th century, the school garden ideology was strong in Finland and the cultivation of useful plants grew into a large scale at Seminaarinmäki as well.

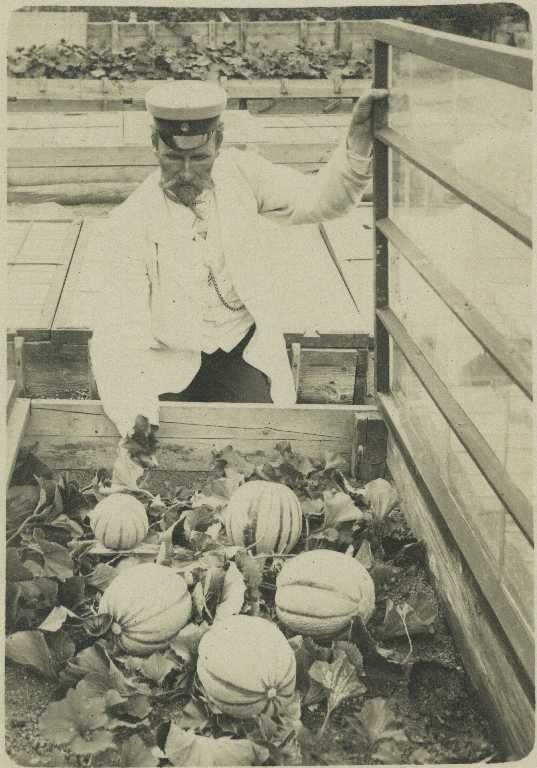

At its largest, the Seminaarinmäki school garden featured more than 1,000 berry bushes, extensive vegetable gardens and a highly productive orchard. The harvest of the garden was used in the Seminary kitchen, but a part of it was also sold to the townspeople in the marketplace. The sales from the Seminaarinmäki garden included at least green plants, forced bulbs, berries, fruit, vegetables, bouquets as well as seedlings and flower soil. The state also aimed for increased apple farming in Finland and the dissemination of related knowledge across the country also through the Seminary teachers and students.

Seminaarinmäki Park also had a greenhouse since the 1880s. The original wooden greenhouse was dismantled in the beginning of the 20th century. Based on W. Polon’s plans, a new one was built (1901), which was later expanded (1928). The Seminary greenhouse was used particularly for growing green plants and forcing bulbs to flower in winter. Green plants were grown to be placed in classrooms and to provide learning material for science education. Up until the 1960s, a greenhouse was located in the garden of Villa Rana (1905) designed by Yrjö Blomstedt. When gardening instruction ended in teacher education in the 1960s (at the College of Education), the old greenhouse was dismantled. It was located on the slope next to the wall of the present Villa Rana garden.

After Finland gained independence, science education and gardening belonged to the curricula. Seminaarinmäki Park entered a highly active phase. For example, beekeeping experiments were conducted with varying degrees of success, and the plant species were diversified. The golden era of Seminaarinmäki Park can be dated to 1891 to 1934. Still in the 1930s the park was considered the most beautiful one in the town and was very well maintained. However, functionality gradually came to be seen as a key value for parks, and the placement of these functions began to affect the structure of the old landscape park. Increasing food production also became increasingly important after the years of hunger faced in the first decades of the 20th century, and the farming of useful plants therefore took up more and more space.

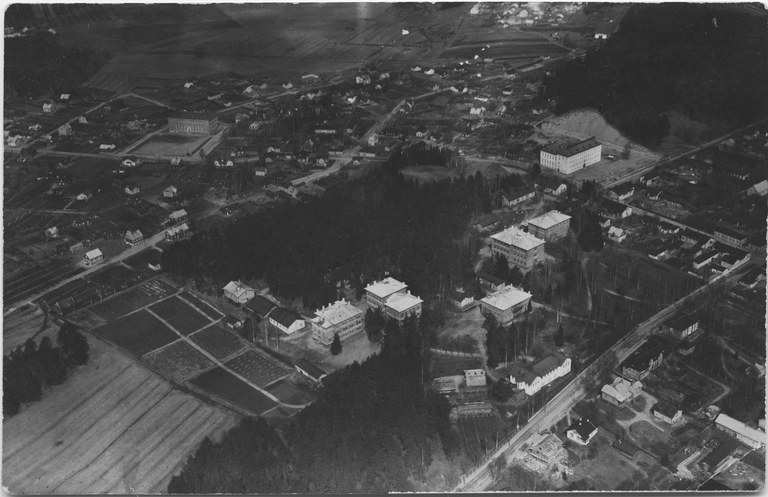

The era of Jyväskylä College of Education and the University

In 1934, the Jyväskylä Teacher Seminary became the tertiary-level Jyväskylä College of Education, which resulted in a new facility needs. The war years from 1939 to 1943 were challenging for the park harshly as the garden went untended for several years. However, the garden was rehabilitated especially through student work, but the additional construction from the 1950s onwards toward the former fields of the Mattila farmhouse (southwest from Seminaarinmäki) changed Seminaarinmäki Park into a building site for several years. The old vegetable gardens and wooden buildings were demolished, and the local emphasis shifted to the new campus area designed by Alvar Aalto.

In accordance with Aalto’s plans, a wall was built to separate the old school vegetable garden and greenhouse (Villa Rana garden) from the lane leading to the campus area designed by Aalto himself.

When, in 1966, the Jyväskylä College of Education became the University of Jyväskylä, and educational activities were moved fully indoors, gardening instruction ended. The greenhouse on the Villa Rana slope was torn down in 1969 and the old Seminaarinmäki Park had to adjust to Aalto’s campus design. Yet, some cultivation of useful plants was still maintained on campus up till the 1970s and the part was tended as an ordinary greenspace, with no educational purpose.

The period of complementary construction

The old Seminaarinmäki Park was further split up by the complementary construction amid the old Seminary buildings in the 1970s. This construction work was originally planned by Alvar Aalto but were passed to Arto Sipinen after Aalto gave up the project due to the significant resistance he encountered. The new buildings designed by Arto Sipinen met similar resistance, which led to a so-called park battle with heated debates for and against the project. People were worried that the old Seminaarinmäki Park would now be destroyed for good. A compromise was reached when the planned site of the Library was moved a few metres toward the city centre and some old trees could be preserved. The new buildings designed by Arto Sipinen brought long-awaited relief to the University’s facility problems and were thoughtfully situated onto the Seminaarinmäki slope. Nevertheless, the complementary construction destroyed the main landscaping elements of the old Seminaarinmäki Park and broke the park area up once and for all.

In 1974, Professor Mikko Raatikainen from the Department of Biology proposed that a new kind of greenspace garden be established to support biology teaching. The greenspace garden was a variant of the botanical garden and its actual planning started in 1980 with a related general plan (by Virve Veisterä). At this early stage, Seminaarinmäki was regarded as the most central area for the plan. The plan was extensive and it was never fully implemented even on Seminaarinmäki, except for the renovation of the new Moirislampi Park on city-owned land.

In 1989, the University established a coordinator’s post for the greenspace garden, and the University’s greenspaces received the official status of botanic garden in 1990. The ridge landscape and the remains of the school garden at Seminaarinmäki were constantly being threatened, however, so the then Finnish National Board of Building ordered a land use plan of the University of Jyväskylä, the main goal of which was to defragment the landscape image of the area. Accordingly, in the late 1990s some parking places, lanes and plants of the area were rearranged.

The construction of Mattilanniemi Park designed by landscape architect Juhani Rajala started in 1984 when the complementary building project advanced to Mattilanniemi and the new buildings were completed. The northern part on the city side was designed by Irmeli Kurttila, drawing partly on Rajala’s greenspace plans. Most plantings in the park area were made at the beginning of the 1990s, developing thereby extensive plant collections in the area. Ylistönrinne was built on the opposite side of Lake Jyväsjärvi starting in the 1990s. The construction was concentrated on the slope while the strand was left for a path. The first plantings in this area were made in summer 1991 according to Juhani Rajala’s plan, whereas the plantings surrounding the buildings were designed by Architect Office Sipinen.

Changes of the 21st Century

The new century has brought big changes to JYU Botanical Garden. The esteemed first coordinator of the Botanical Garden, Hillevi Kotiranta, retired in 2015, and along with the revised Universities Act in 2010, the ownership of the campus area was transferred to University Properties of Finland Ltd. In addition, a holistic renovation and restoration of the park area at Seminaarinmäki began in 2012. Related planning by Maisemasuunnittelu Hemgård Oy was based on detailed historical, landscape and environmental surveys.

The renovation started from the oldest part of the park, continuing later to Aalto Park. The leading idea in the whole renovation project was to preserve and protect the endangered features of a landscape park as well as the historical plants and layers on Seminaarinmäki. In 2022, the University regained a coordinator’s post for the Botanical Garden. Furthermore, in April 2022 the European Commission awarded the European Heritage Label to the Seminaarinmäki campus of the University of Jyväskylä, the first recipient in Finland and in the Nordic countries to do so.

- Further information:

The University of Jyväskylä received the European Heritage Label, June 2022

References and additional information in the following publications: - Mari Forsberg: 125 vuotta Seminaarinmäen puistoalueiden historiaa [125 years of history on the Seminaarinmäki park areas] (Publisher: Alvar Aalto Foundation, Alvar Aalto Museum, Senate Properties 2008)

- Anna Karjula: Jyväskylän seminaarin puutarha ja Seminaarinpuisto vuosina 1863–1934 [Jyväskylä Teacher Seminary Garden and Seminary Park in years 1863–1934] (Master’s thesis, University of Jyväskylä 1998)

- Jussi Jäppinen (ed.): Pikkukaupungin pihoja ja puistoja. Kaupunkivihreän kehitysvaiheita Jyväskylässä [Yards and parks of a small town: Development stages of urban green areas in Jyväskylä] (Publisher: Jyväskylän Puutarhaseura, Jyväskylä Seura 1996)

<>

WELCOME TO THE JYU BOTANICAL GARDEN!

The outdoor areas are open for everyone at all times, and you can find plant name plates especially on Seminaarinmäki and in Aalto Park.

View or print a map from here for a self-guided tour in the Seminaarinmäki garden.

Starting address: Seminaarinkatu 15, 40100 Jyväskylä.